A trans and lesbian garden.

This temporary project ends in 2025, to save the plants growing here we organise a series of queer gardening Sundays. Please find out more about this here: https://elinedc.blogspot.com/2025/01/gesamthof-trans-lesbian-garden-2019-2025.html

The Gesamthof

is an art - nature project in Antwerp between the walls of an old monastery. This garden is inspired by the books by ecofeminists and other writers, like Anna Tsing, Donna Haraway, Robin Wall

Kimmerer, Jamaica Kincaid, Virginia Woolf and many others. They're possibly not all lesbians, but they changed the

way to see a garden: a garden can be a place where culture is part of nature and

where people care for an ecology while humans are not in the centre. Below you can read notes on the short film, find photos of the garden (you can see more photos on instagram's profile wool_publishing) and read about this project as well as the garden recipe, at the end of this page you will find a reading list of influential books related to the topics of gardening, gender and identity.

The Gesamthof, a trans and lesbian garden, supports minorities in local ecologies, this garden is home to wild plants, birds, insects, fungi and all kinds of critters playing part in nature. Instead of buying cultivated plants that are adapted for economic profit, we prefer to grow the wild species bought at specialised local nurseries that support ecology. Recognising the connection between different axes of discrimination we come to this garden to learn to think with other species and garden together.

|

| The entrance to the Gesamthof, with a notice board informing about the non human centred approach. |

|

The Gesamthof in the summer of 2021

|

|

The monastery garden in early spring 2019, after removing a lot of brambles and nettles.

|

|

In 2021 the monastery garden was an archipelago before we had to install a fence between the human and non human centred areas.

|

|

The Gesamthof is a city garden, wild plants from all parts of the world come together.

|

|

| The city ecology works as one big garden as a mosaic all over the city, in pockets of safe spaces. |

About the Gesamthof

Because it is a non-human centred garden the

Gesamthof doesn't need to be beautiful, it doesn't have to produce food and it's not about giving people more space. It's a

place where

the soil, water, air, bacteria, protoctists, fungi, plants and animals

all have

equal rights and people are caretakers. Rewilding within a city can't

become a balanced nature all by themselves, the buildings and traffic favour species like

brambles, elderberry and buddleia and vacant soil is unable to become

diversified without a bit of help.

The Gesamthof aims to be an effective ecological safer space, a place

where we

restore nature while we are aware of what is connected to the soil and

botany:

the economics of gardens, the colonial past and patriarchal classification of nature. The

Gesamthof is a

place where by restoring nature we learn to recognize the past and

present and how we all have a responsibility in this layered story.

The Gesamthof is a lesbian garden, a place that thinks and exists from a minority perspective on inclusion. Everyone is welcome to

visit the garden, this project is focused on

diversity in all kinds of ecologies. From my own experience as a lesbian I noticed a lack of

representation, not that there wouldn't be any lesbians in the art

world (there are lots) but the topic remains precarious and difficult to

talk about. The word 'lesbian' is still an awkward word, people don't have an easy association about what this lesbian garden might be. There are many answers to what might be a lesbian garden, but for sure it is not a zoo. This project doesn't mean to label people to fit within a

category; 'lesbian' is used in an inclusive way and means everyone who

identifies as a woman; trans, neutral, gender non conformed and cis.

|

The Gesamthof in 2020, full of little garden projects.

|

The

Gesamthof is a

young

garden under construction, it started in 2019 with a botanical

archeology: what life was to be found in the soil? Since then the garden

is botanically inspired and we're working towards a diversity of wild

plants from all over the world. To make sense in the 21st century we

needed to invent our own recipe for gardening, adjusted to the city and

bringing ecology in bite sizes: a Gesamthof recipe.

|

Sphagnum moss is growing in a bucket with a swamp construction.

|

The Gesamthof recipe

A lesbian garden.

The

Gesamthof is a non-human-centred garden, it

is a garden without the idea of an end result and it is about working

towards a healthy ecology. This recipe shares how we garden in the Gesamthof.

Rest, observe.

Start with 'not a thing', it is the quietude before one begins. Rest as

in ’not to take action yet'. I find this a good begin, it has helped me

many times. When I plan to work in the garden I put on my old shoes,

take a basket with garden tools and the seeds to sow, and I open the

gate and step into the garden and - stop. Not to act at once, but to

wait a moment before beginning gives me time to align myself with the

soil, the plants, the temperature, the scents, images and sounds. I look

at the birds, the snail, the beetle on a leaf. I walk along the path

and greet the plants and stones. Like me, in need of a moment, they too

need to see who entered the garden. I know the plants can see me because

they can see different kinds of light and they grow towards light and

they see cold light when I stand in front of them casting my shadow on

them. They can see when the sunlight returns and I moved on. This is the

first connection with the garden: to think like a

gardener-that-goes-visiting. Donna Haraway writes about Vinciane Despret

who refers to Hannah Arendt’s Lectures on Kant’s Political Philosophy;

'She trains her whole being, not just her imagination, in Arendt’s words

“to go visiting.”' all from the book Staying With The Trouble (see the

reading list below). Sometimes it is all I do, and time passes, for an

hour and more I feel truly alive with listening, feeling, scenting and

seeing. I can taste the season.

Your senses & your mind.

To feel as well as to think along with nature. This is perhaps

the hardest to explain, but this is the way I learned to garden from

when I was helping as a volunteer in the botanical garden in Ghent. While there is a lot to learn and to remember: you can look it up most of the

time. There are plenty of books on what kind of plant likes to live in

what kind of conditions. Those facts are easy to find. For me, the

rational explanation comes in the end, like a litmus test to see if a

theory works. I like to begin with experiencing things: feeling the

texture of a leaf, noticing the change in temperature when it's going to

rain, comparing soil by rubbing it between your fingers, smelling soil,

plants, fungi and so on. Senses connect us to all kinds of

matter in a garden and they help one to become part of the garden.

Donna Haraway writes about naturecultures, an interesting concept to

rethink how we are part of nature and how the dichotomy of nature and

culture isn’t a real contradiction. It is an argument to stop thinking

as 'only human' and start becoming a layered living togetherness. It’s in our

best interest to feel nature again with our senses. At the same time,

be aware that many plants are poisonous and/or painful, they might hurt

you so don’t trust your instincts too much without consulting facts.

Gesamthof, a non-human-centred garden.

The

patch of soil I consider as the shared garden, the Gesamthof, is part

of a planet full of bacteria, protista, fungi, plants and animals and all of these enjoy being in the garden too. I

try to give the fungi some dead wood to eat, and I don't use herbicides

and pesticides while caring for the plants. This is kind of obvious,

it's basic eco gardening, but it also concerns the benefit of the entire

garden. The important question is: who is getting better from this?

When I count in birds, insects, plants and fungi and the needs

they have to survive in a city, then a small garden is for the benefit of all

of these and the ruined artichoke isn't much of a disaster, many big and small gardeners enjoyed being with the artichoke, drinking the nectar, eating the leaves, weaving a web between the dried stalks. Thinking of all us gardening together changes the purpose of the garden, it's no longer focused on humans only. Often I see a seedmix for bees in the garden centre, but every garden has a different relation to bees, sometimes with solitary wild bees living of a single plant species not having any interest in a human selected seed mix with a colourful flowers display. The question "Who is getting better from this?" stops me buying things for my pleasure and teaches me to be happy when a healthy ecology is establishing.

Thinking like this has made me question the situation

of indoor plants. If they could chose between living inside a house in a

cold country or being outside in a warm location, wouldn't

they prefer to sense the sunset and feel the wind in

their leaves? Am I keeping plants in the house for my own benefit?

Would plants grow in my house if I didn't water them and look after

their soil? Should I put plants in places where they naturally wouldn't

grow? I have decided not to buy new plants for in the house, I will care

for the ones I am living with as good as I can. Does the garden end at the door? Or do I live in the garden too?

The diversity of city life in a garden.

The

opposite of local wild nature is not a foreign plant, but a cultivated

plant. The garden combines native plants from many continents, I grow

African lilies next to stinzen flowers and local wild plants; they get

along well. I'm not a puritan who wants to grow only one colour of

flowers or only authentic plants, I see the garden more like a city

where we arrive from all corners of the world. Plants don't know

borders, they don't care for nations, if they like the place they'll

grow happily. But humans don't always know what they are planting and we

build so much & take away so many plants and replace the green in

our gardens with other varieties, often cultivars that don't interact

with local species. A cultivar is the opposite of a wild plant, a

cultivar is selected for a quality liked by humans but not always in

regards to the ecology with other species. Some cultivars are great

plants, they are strong and beautiful and interact in symbiosis with the

rest of nature. But some cultivars blossom at the wrong time to attract

insects, or they don't provide anything for the others to interact

with. In other words, they are planted to be pretty and not to take part

of a wholesome nature. Because of these cultivars we are rapidly losing

authentic genomes of plants that are important to preserve nature. When

you have a garden that is designed and planted with only these kind of

cultivars you don't invite nature in. You might just as well have

plastic flowers. The opposite is to care very much for the diversity of 'pocket' nature, what was growing in this pocket of the world, and

to try to find old species specific for this area that have been around for

thousands of years, and have become an important sustainable link within

the local ecology of insects, plants, fungi and other living beings. I

let the weeds grow in the garden to support the network of insects needing

those plants, and birds needing the insects, and local plants needing

these insects and birds as well and so on and so on. The gardens in a

city are like corridors, they connect insects, plants and fungi into a

greater network that is necessary to sustain these species. While we see walls and hedges around a garden, and we might think of it as our island, it is part of a larger green archipelago where plants, birds, insects and others are not hindered by walls. Every city has only one garden made up of all these green islands just a few streets apart.

We shouldn't break this chain of connected nature by losing our interest in local wild

plants, often seen as uninvited weeds and taken for granted, they are

very important in a diversity that expands with every living species.

Since we're living in a time of mass extinction & losing multiple

species every day, all the things we can do count and in a

garden we can let nature in. Sometimes I buy organic local

plants from small nurseries to support their effort for conservation.

But there is very little money involved in the Gesamthof. When I started

to work in the garden I got many plants, seeds and cuttings for free

and in return I also like to give away sister-plants so the Gesamthof

lives on in other gardens. This is how plants from all over the world

became part of the Gesamthof, and they all are very important in the

diversity of the garden. There are Spanish bluebells and a Chinese

Wisteria that were planted by the monks from the monastery a long time

ago, they survived decades of neglect, there are Evening Primroses that

most probably arrived on the wind from neighbouring plots and there are

colourful tulips, both wild and cultivated that attract all kinds of

human and non-human visitors.

The garden will help you.

This

is the strangest thing, but since I'm working in the Gesamthof, plants

have arrived from all kinds of places, they have often been given to me

for free. Also garden materials, pots & books seem to come without

much effort. They arrive from lots of generosity from others. I work in

the garden, but not to create 'my garden', I see the garden as its own

entity and I'm 'the one with arms and legs' who can help where needed.

Many other living things help as well. Wasps have been eating the

aphids, Cat's Foot (Glechoma hederacea) is keeping my path free from

weeds and the Titmice eat the spiders that make a web on the garden path

(thank you, I don't like walking into spider webs). I'm one of the

garden critters (a word I borrow from Donna Haraway, critter isn't as

attached to creation as creature is) and I love seeing the other critters thrive at their work. I'm not doing this alone. While I do put in a lot of work, I see it as a part of my artistic practice. Gardens are often not seen as an artwork, but to do research, to add a different perspective, to engage with the soil, water and living beings, to build a different kind of place and share this as a public work is very much how I see art work. Art can be more than making and showing things, it can be interaction, awareness and sharing too. The Gesamthof works without

a financial set up, it is thriving by generous neighbours who share

their plants, seeds, helping hands and advice. This garden is giving

more than it costs.

Don't make a garden design.

This might sound

counter intuitive, but being in the garden very often, one should know

what the garden needs and that should be enough of planning. The usual

garden plan is often seen as to give shape to the idea of an ideal garden,

with a sketch of what to plant where, what colours to combine, where the

path should be and in what material and so on. It would mean to put oneself above all else as the creator, and it means setting oneself a goal

to work towards, with in the end a 'beautiful garden'. I don't think

gardens should be 'made' beautiful, just like human animals shouldn't be judged on a scale of beauty. It's a binary opposition, a way of

thinking that leads to a lot of suffering both in and outside of the

garden. Instead let the garden take the lead and follow in their steps.

You find a plant that likes a sunny area, put it in the sunny part of

the garden and it will thrive. Do you have a lot of bare soil in the

shady area and you don't know what to do with it? Look up shady plants,

find a nice variety and let it grow in your garden. Do you need a path

between the plants? Add the material that works best in that place (for

instance a forest kind of material would be tree bark, and recycled

materials also make excellent paths). This way you're growing a

cultivated wild garden that will be beautiful all by itself just like

nature is. Use creativity in how you arrange stones along a path, in how

you support plants that will fall over, in how to add water and feeding

stations, in creating fine labels, in making drawings that will later

on help you to remember what you planted where... there is lots of room

for creativity.

Intersectionality & botany.

The

connection between botanical classification systems and people

classification systems illustrates how the same mode of thinking is

applied to both our gardens and us as people. Botany is full of anthropocentrism and it is not bad to be aware of this, the lesbian garden reframes this use of gardens. Suddenly the invisible norm of who usually benefits from gardens is no longer in place. 'Lesbian' means nothing if it is not connected to racialized people, to class differences, to living with disabilities, to age and all the other aspects gathered in Kimberlé Crenshaw's intersectional theory. To put intersectionalism

into practice means asking the 'other question': who benefits from this

garden?

- Bees opens up the discussion on native plants, their genomes and diversity in gardening.

- Plants opens up the discussion of the colonial past, systems of economics, and who has a 'right' to extract.

- An audience that visits art spaces

(the Gesamthof is accessible trough the Kunsthal Extra City) opens up

the question of class, inviting the 'other' in, lgbtqi+ friendly spaces

etc.

- Me opens up the question of access & responsibility that comes with privilege.

To

ask the other question means that we are aware of others. Is the Gesamthof appropriate

for children? Should it be? Should we take out all the poisonous plants,

the pond, the bees hotel etc if we want children to be safe? There is a

fence around the Gesamthof to keep wandering people out, because the

garden is certainly not safe for everyone and not everyone is safe for the garden.

Atemporal gardening.

Every

place carries a past into its future. The past is not a distant island,

it's very much with us in this thick present (again Donna Haraway's

words, the thick present is like a composted layered presence). In my

garden I don't want to be blind for what is present from the colonial

past. It takes effort to find out how all of this is linked, how the

history of botanical gardens is woven into to the need for classifying.

It is hard work to learn about colonialism and gardening because it's

not as clearly visible as for instance plantations and slavery are

linked to cotton and coffee. A garden is often more like a collection of

plants bedded into a designed space and the colonial past is not a

comfortable topic in garden programs. It takes visiting the past to find

out what is here today. For me it meant going to the botanical garden

in Meise and looking at the plants brought back from colonies. It also

meant digging in the past of the Gesamthof's location in the monastery,

who was gardening here before me? How can I work with ecology towards a

better understanding?

Note:

People suffer from plant-blindness (J. H. Wandersee and E. E.

Schussler, publication 'Preventing Plant Blindness' from 1999), it means

we don't see the plants that we don't know and by giving garden tours

one can share the awareness of this cognitive bias. In a lesbian garden

the cognitive bias rings a bell, without representation people have a

hard time discovering what is different about them. Many lesbians don't

know that they are a lesbian when they grow up, and they see themselves

trough the norm of a heterosexual society while a part of who they are

remains empty for themselves. Like plant-blindness, this abstraction of a

norm can be countered by looking at the differences as positive

characteristics.

Ongoing change.

A

garden is a nice form of art & activism, it is a healthy activity that helps

to relieve stress and anxiety. It is working towards change by educating

one's self and each other, it is becoming aware of nature and changing

our way of thinking. It is pleasant: the scent, the view, the touch, the

sound, it's a nice place to be. I become very aware of the moment when I

sit in the Gesamthof. Time passes differently for all the inhabitants

and visitors, and some of us spend a lifetime in this garden (most of

the pigeons do) while for me it is very temporary. I will miss the

Gesamthof when the new owners arrive in the monastery. But it doesn't

make it less worth it, on a larger scale gardening means ongoing change,

and we can enjoy every moment of it. Never is a garden a fixed thing,

it is never finished and there is no 'end', it just moves into different

places.

If you would like to get involved on the

Gesamthof recipe, you can find it in a communal document that allows

your input and experiences. This link leads you to the framapad

Gesamthof recipe and feel free to add your garden ecology comments here:

Gesamthof recipe

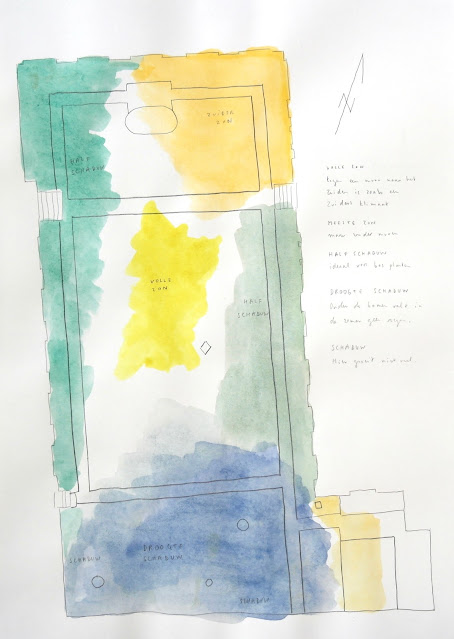

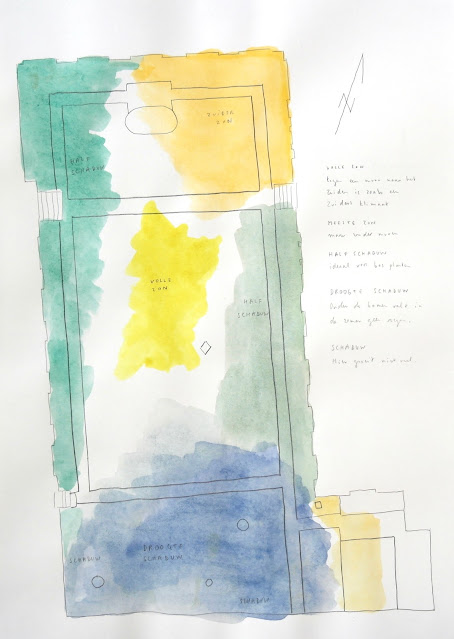

The Gesamthof ATLAS

In

2020 Extra City moved into the church adjacent to the hof where we have

our garden project. Structural changes required looking into the use of

the hof. In correspondence with AAIR, the organization looking after

the artist studios and residencies, and in conversation with the

artists residing at the studios we decided it would be good to have some

document that explains the workings of the garden: the ATLAS.

In

the winter of 2020 - 2021 the different maps of the ground are

pencilled down, with the plant locations, the rain shadow, the path of

the sunlight as it moves trough the garden from morning till evening,

the places where birds nest, the location of pits, paths and compost...

The ATLAS is a series of drawings and watercolours of what the garden looked like in 2020.

|

Ecology and wild life protection areas.

|

|

Rain, sun and shade areas indicate what plants thrive where.

|

|

Direction of the sunlight, cool and hot areas.

|

|

Botanical diversity map.

|

|

Plant list.

|

This

project started out of the potential of the forgotten monastery garden.

The Gesamthof started

without institutional structures or funding, it is made with the

help

of many people and the generous support of the Botanical Garden in

Ghent. The Gesamthof is being developed as an artistic project by me,

Eline De Clercq, to help

artists to be more

aware of our environmental identity and as a learning tool for botanical

information. I decided to make it into a lesbian garden, I did this to

address ecology and diversity among people as well as gardens. I'm not

doing this on my own, many people are involved in this project. There is

no clear answer to what a lesbian garden is, and we are working towards

a multitude of possibilities. We hope this project will grow as a

lesbian garden, as a natural space for

studying ecology within an artist

practice and that it will become home to research, lectures and

workshops. We would like to involve visitors of the art spaces, artists

in residency and the local community. Many thanks to everyone who helped

to make this possible and especially thank you for your help

Plantentuin Ghent and Joris Thoné natuurtuin. This project has been

supported by Morpho, Extra City. Thank you to Katrin Kamrau, Joost Elschot, Iris Carta, Zuzanna Rachowska, Anna Housiada, Samyra Moumouh, Marc Libert, Olivier Dubois, Kristin Morel, Anny De Decker, Joris Thoné, Julia Dahee Hong, Yoko Enoki, Koyuki Kazahaya and many, many others.

The short film: Gesamthof / A Lesbian Garden

Anne Reijniers is a film maker and artist, together with Anne we are making a short film about this garden as an art project. The film is going to be released on 30 July 2022 in Extra city and Morpho. In this time document we follow Eline De Clercq during a garden tour with the Morpho artists in residency. The film shows the Gesamthof, a lesbian garden - including trans

people - inspired by the books of Donna Haraway, Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing,

Jamaica Kincaid, Robin Wall Kimmerer, Ursula Leguin and many other

thinkers who are working on togetherness in the Plantationocene. The

Gesamthof puts thoughts into tangible practice: Haraway's queer kinship, speculative fabulations, situated knowledge

and Tsing's explanation of a complex patchy capitalism and the human

aspect into the restoration of post-industrial land as well as being

part of the ecology. In the garden we see how compost works, what soil

can do and how a pine tree is a great pioneer. In the film we document

the garden and our place in it along the garden path. The tours that are

given in the garden activate the stories that are shared between the

human and nonhuman inhabitants.

The temporary nature of the

garden, the residents and the project, gives this short film an urgency.

We don't know how long we can stay at this location, and climate change

is happening now, both makes us feel like we have to keep working at a

better understanding of what ecology means in a multilayered compost.

On the instagram page of wool_publishing you can follow the changes in the garden.

To visit the garden please contact me via the above instagram page.

Reading list on topics of gardening & lesbian and non binary identity and ecology:

Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life, Duke University Press, Durham, 2017.

Laurie Cluitmans (ed.), On The Necessity Of Gardening - An Abc Of Art, Botany And Cultivation, Valiz, Amsterdam, 2021.

Katy Deepwell (ed.), Feminist Art Activisms and Artivisms, Valiz, Amsterdam, 2020.

Emily Dickinson, Envelop Poems, New Directions, New York, 2016.

Susanna Grant & Rowan Spray, From Gardens WHere We Feel Secure, Rough Trade Books, Londen, 2021.

Donna J. Haraway, The Donna Haraway Reader, Routledge, Abingdon-on-Thames, 2003.

Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble. Making Kin in the Chthulucene, Duke University Press, Durham, 2016.

Donna J. Haraway, When Species Meet, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2008.

Roni Horn, Roni Horn aka Roni Horn, Steidl, Göttingen, 2009.

Gertrude Jekyll, A Vision of Garden and Wood, Published Sagapress Inc, New York, 1990.

Jamaica Kincaid, A Small Place, Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, New York, 1988

Jamaica Kincaid, My Garden (Book), Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, New York, 1999

Ursula Le Guin, The Carrier Bag Theory of Ficiton, Ignota Books, United Kingdom, 2020

Nat Mady & Catmouse, Enjoyin Wild Herbs, Rough Trade Books, Londen, 2021.

Agnes Martin, Writings, Hantje Catz, Ostfildern, 1998.

Hans Ulrich Obrist (ed.),140 Artist's Ideas for Planet Earth, Penguin, Londen 2021.

Claire Ratinon & Sam Ayre, Horticultural Appropriation, Rough Trade Books, Londen, 2021.

Wim Schroevers en Jan den Hengst, Plantenrijk, Heideland-Orbis, Amsterdam, 1978.

Gertrude Stein, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, Penguin Classics, Londen, 2001.

Heleen Touquet, What Values, Whose Values, ASP Academic and Scientific Publishers, Antwerpen, 2020.

Heleen Touquet, Minorities, Belonging and Values, ASP Academic and Scientific Publishers, Antwerpen, 2021.

Anna

Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World. On the Possibility of Life

in Capitalist Ruins, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2015.

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Gatherin Moss, Oregon State University Press, Oregon, 2003.

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass, Milkweed Editions, Minneapolis 2020.

Kitty Zijlmans & Wilfried Van Damme, World Art Studies; Exploring Concepts and Approaches, Valiz, Amsterdam, 2008.

No comments:

Post a Comment